Continuing in our series Utilizing Public Domain for Your Ministry, we examine another public domain work. In this case, both the text and tune are in the public domain. We hope this series inspires your ministry and invigorates your worship!

GO, TELL IT ON THE MOUNTAIN likely began life as one of the spirituals sung by enslaved Foundational Black Americans. Its composer(s) remain anonymous, and probably will forever, because of history long suppressed and erased. In the intervening centuries, though, “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” has become a standard proclamation of the triumph of the Lord’s incarnation, enjoyed by Christians of all cultures.

Credit for popularizing “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” may belong to the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who toured the world in the late 1800s raising funds for Fisk University. The Fisk Jubilee Singers are the golden standard among Black gospel groups: the original ensemble of 10 musicians toured the world giving concerts to rescue the academically renowned, but financially imperiled, Fisk University. Because Fisk University was founded in 1866 to serve newly freed Foundational Black Americans, the ensemble called themselves “Jubilee Singers,” reflecting the Biblical Jubilee described in Leviticus as a year when all slaves would be freed.

These student musicians originally fought against performing spirituals because they viewed the songs as too sacred to perform in the context of secular concerts and because the songs evoked a painful past beyond which the students were eager to move. Ultimately, the Jubilee Singers agreed to sing spirituals as a way of elevating their souls and their ancestors’ talent. “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” was a favorite spiritual of Fisk University students; early every Christmas morning, students would walk from building to building singing “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” to rouse any late sleepers.

The most prominent Fisk University musician to be credited with preserving “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” is John W. Work, Jr. Work taught Greek, Latin, and history at Fisk, as well as performing with and directing multiple ensembles. He wrote, taught, and performed throughout his entire career with the goal of demonstrating that AfricanAmerican spirituals were the “true” American folk music. His seminal publication, Folk Song of the American Negro (Press of Fisk University, 1915), is still an important source documenting a wide range of songs that might have been lost to time without Work’s intervention. It is possible that Work authored the words and set them to a preexisting spiritual melody (the traditional “When I Was a Seeker” bears a number of similarities to “Go, Tell It on the Mountain”).

Another possible “genealogy” of “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” credits the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) with preserving and popularizing the tune. The Institute Press, run by the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, published Religious Folk Songs of the Negro as Sung on the Plantations (ed. Thomas P. Fenner) in 1909, and it is in this book that “Go, Tell It on the Mountain” first appears. Chris Fenner, of Hymnology Archive, points out that in this publication, Thomas P. Fenner does not credit Work, despite clearly labeling other songs in that volume as Work’s. Such an omission seems to suggest that the musicians of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute did not believe that Work authored the words or documented the melody.

Making the question of authorship even more complicated, there are significant variations among the lyrics printed in these early sources. Some smaller differences can be dismissed as the natural result of different people transcribing the same source material as they hear it. However, the version published by John Work III, John W. Work’s grandson, contains completely different verses. John Work III claimed that his father authored the verses himself because no musician could recall the original words of the verses. Such confusion regarding the various texts does nothing to clear confusion surrounding the tune’s lineage. Regardless of which institution deserves credit for “Go, Tell It on the Mountain,” the tune has proven its enduring power through the decades.

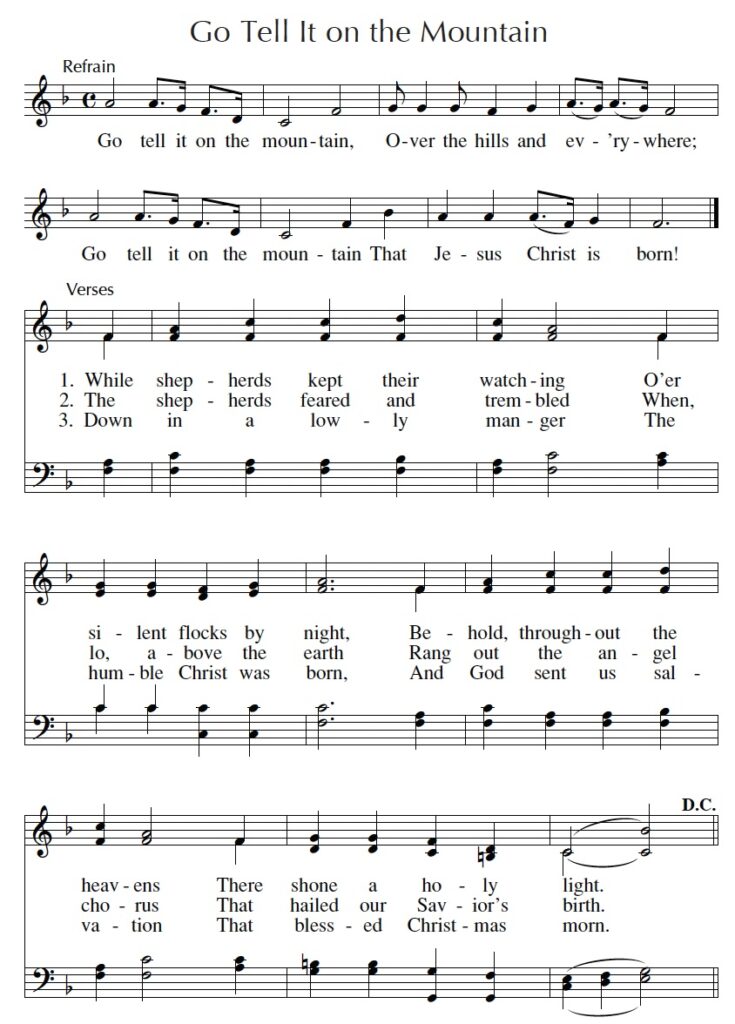

Like most popular songs, this melody is in verse-chorus form. That is, the melody is separated into 2 separate sections: the verse, which has different words each time we hear it; and the chorus, which has the same words each time. The verse and chorus are equal in length, just 8 bars each.

The most striking difference between the verses and the chorus is the change in texture. During the verses, singers sing the melody in unison. In contrast, during the chorus the singers split into 4-part harmony. The melody is mostly pentatonic, using only 5 notes out of the 7-note scale. Pentatonicism is a common feature of folk music around the world, in part because pentatonic scales avoid dissonance.

The verses and chorus are distinguished by rhythm as well. The verse is composed of quarter notes and half notes, and the notes begin and end exactly on the start of each beat and maintain a rigid meter. The chorus, however, breaks into dotted rhythms, dividing the beat unequally to create a sense of bouncing or swinging, and even the occasional syncopation. In addition to giving the chorus a more celebratory effect, these rhythms are especially well suited to imitate the natural rhythms of speech.

“Go, Tell It on the Mountain” is familiar enough that we may take it for granted, but if we listen to the music, we hear the exact moment in which the people in darkness see a great light. What a wonderful representation of our seasonal joy!

Photo by Ryan Conrow: https://www.pexels.com/photo/selective-focus-photography-of-brown-wooden-bench-1178495/